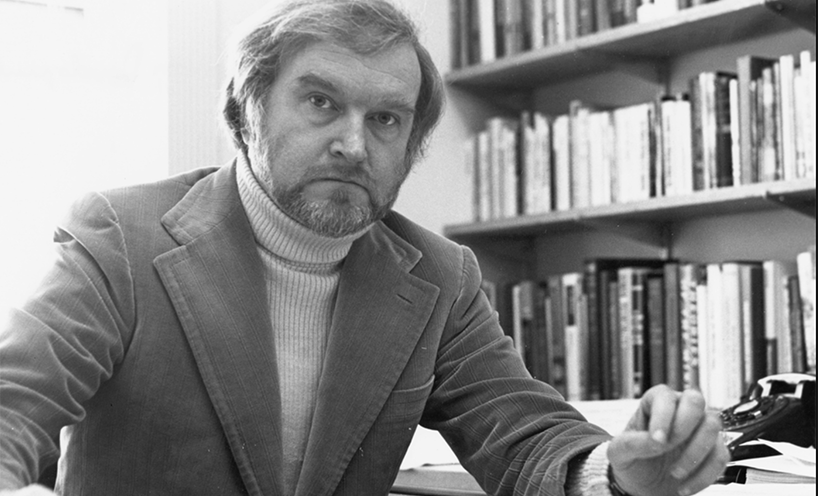

Mihaly “Mike” Csikszentmihalyi, pioneering psychologist, passes away at 87

The “Father of Flow Theory” inspired countless leaders, colleagues, students, and more in his exploration of optimal and positive experiences.

By Sarah Steimer

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi wrote that the best moments in life are not the passive, receptive, or relaxing times. By that logic, the late psychology professor, “Father of Flow ,” author of numerous books, and holder of countless titles — not least among them husband, father, and grandfather — undoubtedly counted many great moments in his lifetime.

Csikszentmihalyi, often known as Mike C. to his friends and colleagues, passed away on Oct. 20 in his home in Claremont, California. He was 87.

“Since his death, so many people have talked about Mike's impact as a person — alongside talking about his impact as a scholar — appreciating his humor, warmth, and generosity,” says Jeanne Nakamura, an associate professor and co-director of the Quality of Life Research Center at Claremont Graduate University. “He was the best example of the things that he studied about the life well lived.”

Csikszentmihalyi was born on September 29, 1934, in Fiume, then part of the Kingdom of Italy and now known as Rijeka in Croatia. His father worked at the Hungarian Consulate in Fiume before being appointed the Hungarian Ambassador to Italy shortly after World War II. The elder Csikszentmihalyi resigned when communists took over Hungary in 1949 and opened a restaurant in Rome. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi dropped out of school to help support the family.

Csikszentmihalyi became curious about happiness after seeing the pain and suffering of Europeans around him during World War II. He found that many were unable to live contentedly after losing their jobs, homes, and general security during the war. The observations led him to become curious about what made life worth living, and he began to explore art, philosophy, and religion as he sought answers.

As a young man, Csikszentmihalyi travelled through Switzerland and — short on the funds necessary for a movie or other such entertainment — opted to attend a talk on UFO sightings. What he stumbled upon was a lecture by Carl Jung, who spoke of the traumatized psyches of Europeans after World War II, and how their mental states caused them to project the UFO sightings into the sky.

The talk piqued Csikszentmihalyi’s interest in psychology, and he moved to the U.S. at the age of 22 to pursue an education in that field. He received his BA from U Chicago in 1960, followed by his PhD from the university in 1965. He taught at Lake Forest College before returning to U Chicago as a professor in 1969, eventually leading the school’s Department of Psychology.

More recently, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi served as Claremont Graduate University’s Distinguished Professor of Psychology and Management. He also founded and co-directed the Quality of Life Research Center, a nonprofit research institute that studies positive psychology, the study of human strengths such as optimism, creativity, intrinsic motivation, and responsibility.

“Mike had a genius for creating simple, generative models of flow, creativity, and aesthetic experience and then unfolding their implications in his writings; the impact of his ideas has been remarkably broad,” says Nakamura, who worked with Csikszentmihalyi for two decades at Claremont to start the Quality of Life Research Center and helped with the launch and nurturing of a graduate program in positive psychology. “The topics are varied but the work all expresses a single perspective on human functioning that was shaped by an unusual life and influences beyond psychological science — history, philosophy, and the arts.”

In Csikszentmihalyi’s exploration into the concepts and causes of optimal and positive experiences, he became intrigued by artists who would get lost in their work — so immersed that they would disregard basic animal cues for food, water, and sleep. Several of his interview subjects described their experiences through the metaphor of a water current carrying them along. Thus, the term and positive psychological concept of a "flow state" was born, along with the seminal 1990 book Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience.

Csikszentmihalyi’s studies on flow included interviews with scientists, athletes, musicians, artists, business executives, and others — particularly creative professionals — because he wanted to know when they experienced optimal performance levels and how they felt. His research led him to conclude that happiness is an internal state of being, and as a matter of external factors.

Individuals, he found, were their most creative, productive, and happy when in a state of flow. As Csikszentmihalyi explained it, flow is “a state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter; the experience is so enjoyable that people will continue to do it even at great cost, for the sheer sake of doing it.”

Much of Csikszentmihalyi's later study focused on motivation and the factors that contribute to motivation, challenge, and overall success in an individual.

The book Flow — which has been translated into more than 20 languages — and its related studies have had impacts reaching far beyond the world of academia. Former President Bill Clinton and former British Prime Minister Tony Blair were reportedly influenced by the book, along with former Dallas Cowboys Coach Jimmy Johnson, who used Csikszentmihalyi's ideas to prepare for the 1993 Super Bowl. In 2004, Csikszentmihalyi delivered a TEDTalk titled “Flow, the Secret to Happiness,” which has more than 6.7 million views.

Among the lives he influenced most were those of his students and colleagues, who offered an outpouring of remembrances upon news of his passing. Karen Skerrett, a psychologist, consultant, author and former student of Csikszentmihalyi's, recalls standing in Green Hall, anxiously awaiting her committee to congregate before defending her dissertation.

“Mike walked behind me and whispered, ‘Be sure you order a nice bottle of wine at your celebration dinner tonight,'” Skerrett says. “In that moment, he communicated his belief in me, helped me get into a positive mindframe, and gather the confidence necessary to get through my defense.

“And I took his advice on the wine.”

Another former U Chicago student, Linda May Fitzgerald, an emerita professor of Early Childhood Education at the University of Northern Iowa, says Csikszentmihalyi offered her two life lessons: take on orphans and write backwards.

“When my UC Human Development master's advisor left before my master's research was written up, Mike generously added me to his roster of advisees,” she says. “And he was there for me again when I needed my doctoral dissertation committee to be filled out. A highlight of my doctoral defense was his participation by calling in — sitting on a rock above Aspen, Colorado.”

When Fitzgerald became the coordinator of the doctoral program in Curriculum and Instruction at Northern Iowa, she says she gladly took on advisee “orphans” similar to herself — “all of whom broadened my perspectives and enriched my life beyond my narrower specialties.”

Jennifer A. Schmidt, associate professor and director of the Program in Educational Psychology and Educational Technology at Michigan State University, says Csikszentmihalyi profoundly altered the trajectory of her life — even prior to meeting him. She stumbled upon the book Flow as a recent college graduate with a psychology degree, finding his work to be “like a flashlight in a dark tunnel,” helping her locate a path forward for herself in the field. She reached out to Csikszentmihalyi, who not only took her call, but invited her to U Chicago to meet, then offered her work on one of his research projects.

“As compelling as ‘my’ Mike story may be, there are dozens just like it,” Schmidt says. “People were drawn to Mike from all corners of the world for his creativity, his insight into the human condition, his preference for studying assets rather than deficits, and his ability to make academic writing truly engaging. His legacy lies not only in his theoretical and methodological contributions, but in the way he invited others into the conversation. His influence on the field of psychology, and on those enough fortunate to have worked with him, is enduring.”

In 2009, Csikszentmihalyi won the Clifton Strengths Prize. He received the Széchenyi Prize at a ceremony in Budapest in 2011 and the Grand Cross Order of Merit of the Republic of Hungary in 2014. Csikszentmihalyi was a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and a member of the National Academy of Education and the Academy of Leisure Sciences.

Csikszentmihalyi is survived by Isabella, his wife of 60 years and a professional editor who also edited and co-edited some of her husband's books, and sons Christopher — an artist and professor of Information Science at Cornell University — and Mark — a professor of philosophical and religious traditions of China and East Asia at the University of California, Berkeley. He was also father-in-law to their respective partners Gemma Rodrigues and Annie Hope, and grandfather to Emily Isabella, Henry Stephen, Kinga Jane, Aschalew Alexander, Zofia Rose Krystyna, and Iris Althea Diana Isabella.

In lieu of flowers, contributions may be made to the Center for Biological Diversity (www.biologicaldiversity.org) and Habitat for Humanity.

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO