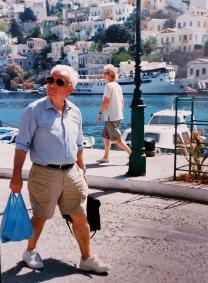

Walter Kaegi, noted scholar of Byzantine and Roman Empires, 1937-2022

UChicago historian was well-traveled, well-loved by generations of mentees and colleagues

By Sarah Steimer

Prof. Emeritus Walter Kaegi visited every province that had constituted the Roman Empire. He spoke Arabic, Armenian, French, German, Greek and Latin, and had a reading knowledge of several Slavic languages. He was the author, co-author, or editor of about 30 books, and wrote more than 100 articles on a wide range of topics.

Kaegi died Feb 24. at the age of 84. A teacher and mentor for three generations of historians, the University of Chicago scholar is remembered as a great collector of knowledge and perhaps an even greater distributor of what he knew.

“My most prominent memories of him will always be as a mentor, a guide and a raconteur,” said his former student Ari Bryen, AM'03, PhD'08, now an associate professor of history at Vanderbilt University.

As a historian at the University of Chicago and Oriental Institute, Kaegi was noted for his scholarship on the Byzantine and Roman Empires, along with early Islam. Over half a century, his work notably integrated a wide variety of sources, and referenced various cultural and scholarly specializations. He drew on insights from military, religious, visual arts, numismatic, and other cultural perspectives. Kaegi was known not only for his voracious exploration of scholarly concepts, but of the world itself.

“Possibly exaggerated rumors that Walter worked for the CIA were only fanned by the numerous chance encounters that colleagues and students reported with him at various locations around the globe,” said Jonathan M. Hall, a professor in the Departments of History and Classics. “Mine was—if I remember correctly—at Schiphol Airport, Amsterdam, when my frantic dash from one part of the terminal to the other was stopped dead in its tracks when I heard a familiar, ‘Hello, colleague,’ from behind me.”

Kaegi was born in New Albany, Indiana, and spent most of his childhood in Louisville, Kentucky. He was drawn to history at an early age and even invented historical games with his grade school friend (and eventual infamous gonzo journalist) Hunter S. Thompson, who later gained fame as a gonzo journalist. As boys, the two self-published a newspaper, The Southern Star, and shared correspondence about military history into adulthood.

Kaegi knew that he wanted to be a historian and decided—by the end of high school—that he would focus on the Byzantine Empire. He received his undergraduate degree from Haverford College and his Ph.D. from Harvard University.

Kaegi joined UChicago’s history faculty in 1965, teaching at the school for 52 years before retiring in 2017.

Through his stewardship, UChicago came to be regarded as a leading center for research and instruction in the late- and post-antique Mediterranean and Near East.

A military historian of the early Byzantine world, Kaegi's early career focused on the Byzantine and Roman Empires, and how they coped with decline. He learned Arabic in his early 40s, leading him to gain new insights from Arabic language sources and redirecting his scholarly focus. The latter part of his career settled on the expansion of early Islam, especially into North Africa at the expense of the Byzantine Empire.

Kaegi’s research was distinguished by his detailed knowledge of geography, thanks to his extensive travel to the regions in question. He drew on literary sources as the primary evidence for military action and carefully studied state infrastructure.

Through workshops and other venues, Kaegi helped bring together faculty and graduate students from a variety of disciplines and departments. He was a voting member of the Oriental Institute, and oversaw the renewal of Chicago’s program in ancient history. In 2021, he was even commissioned a Kentucky Colonel by Governor Andy Beshear.

Atop all his scholarly achievements, he was also a dedicated and supportive mentor and advisor to graduate students, who remember him for his warmth, humor, and willingness to draw back the curtain on life in academia.

“Walter was a remarkable mentor,” Bryen said. “He had a remarkable knowledge of the profession, and was keen to share with his students his deep knowledge of the academic landscape that helped contextualize books and ideas within a long trajectory of scholarship, of personalities, and of broader historical currents. More than once he guided me away from — or at least pointed out — dangerous disciplinary waters, which, to a student unfamiliar with the intricacies of academic politics, was advice worth its weight in gold — or, as it happens, fellowships.”

Bryen and other former students noted Kaegi’s ability to deftly guide them through the intellectual and social mazes inherent to the profession.

“He taught me how to navigate academia, about its power structures and how to work successfully within them, what was worth doing and what should be avoided; how to become a professional scholar,” said Todd Hickey, AM'92, PhD'01 now a professor of ancient Greek and Roman studies at the University of California, Berkeley. “He loved to talk, and if you were patient enough to listen, the advice and information were priceless. Accompanying this practical support was an exceptional kindness.”

His ability to help others move carefully and successfully through academia didn’t stop with graduate students — he also extended this kindness to fellow scholars.

“Walter was my first point of contact with the University of Chicago,” said Hall, who joined UChicago in 1996 from the University of Cambridge. Soon after Hall's plane arrived from the United Kingdom, Kaegi treated him to dinner at the Quadrangle Club. “The sheer amount of information—mainly, though not exclusively, about the University—that he conveyed to me over two courses was mind-boggling … but it also betrayed an ardent wish to ensure that I was as prepared as I could be for the next two days of meetings, interviews and presentations.”

In 2017, his students and fellow scholars collaborated on a book in his honor: Radical Traditionalism: The Influence of Walter Kaegi in Late Antique, Byzantine, and Medieval Studies. When the Kaegi family sold their house, they took photos of the bookshelves and offered volumes to Kaegi's former students and colleagues, who divvied everything up.

“These people from different generations knew each other both because they're in the same field, but also because they worked with him,” said Kaegi's son Chris. “He brought together all these diverse perspectives and disciplines, and was a true multidisciplinarian. I appreciated it, too, in managing that process — that all these different specialists were interested in different parts of his library.”

Reminiscing about his father, Kaegi's son Fritz recalled the "special twinkle in his eye when you could tell he was proud of something."

“It could be a really small matter; you could tell that he loved that his famous Russian fur hat—which he wore everywhere because his ears got cold—was one of the objects of the 1999 Scav, UChicago's annual scavenger hunt. "Or it could be a matter of great principle, such as the vital importance of personal integrity to historians. A very common element was that twinkle had to do with his students, colleagues, and his life at the University.”

Kaegi didn’t discuss his work much at home, said Chris, but the family was surrounded by the physical manifestations of his interests: countless books on a broad range of topics and objects from his travels abroad.

“(Our parents gave us) a real respect, a desire for knowledge — and continuous knowledge, learning different perspectives,” Chris said. “My brother and I both were given real gifts from our parents in those senses: in books and in rich conversations at the dinner table.”

When the family was selling the house, they took photos of the bookshelves and offered the volumes to Kaegi’s former students and colleagues, who collaborated on divvying everything up.

Kaegi was preceded in death in 2018 by his wife, Louise, a Peace Corps volunteer in Tunisia whom he had met through their shared interest in the Middle East. The couple lived for two years during sabbaticals in Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco. Kaegi's two brothers, Richard and George, are also deceased. He is survived by his son Fritz and daughter-in-law Rebecca; his son Chris; three grandchildren; and his sister Karen and and brother-in-law Tom.

A memorial will be held on March 26 at 10 a.m. at St. Thomas the Apostle Church in Hyde Park. Questions and arrangements can be made through Cage Memorial in South Shore. Kaegi will be laid to rest in a private ceremony at Cave Hill Cemetery in Louisville.

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO