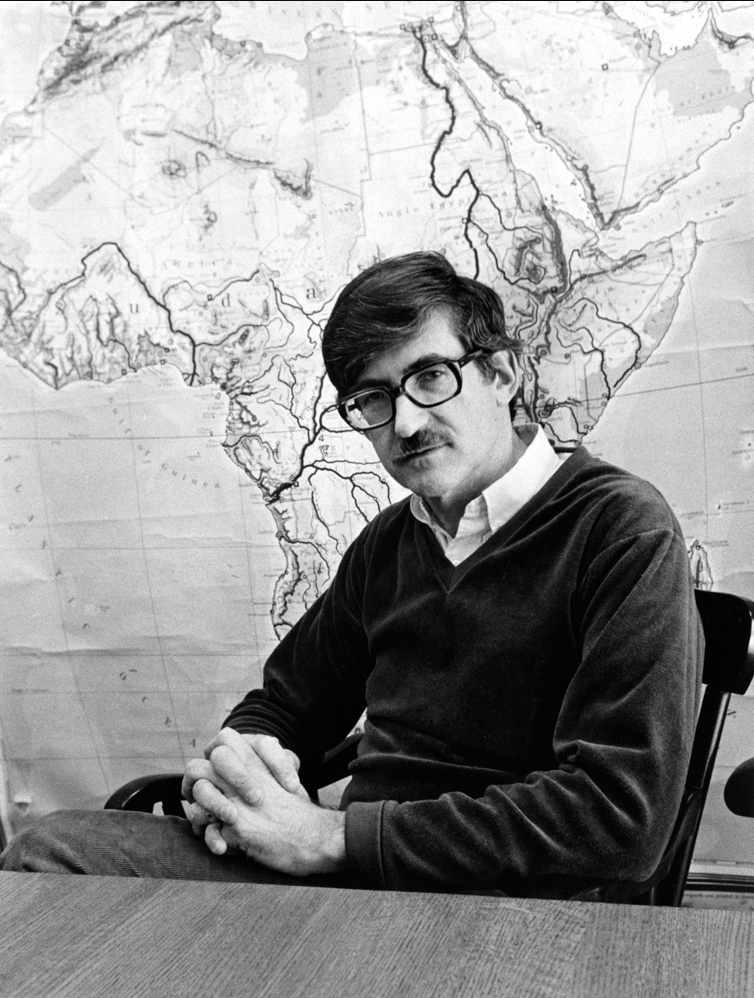

Ralph A. Austen, African Studies professor and a ‘scholar’s scholar,’ 1937-2024

The late academic was a champion of UChicago workshops, a deeply curious individual, and a dedicated family and community man.

By Sarah Steimer

Ralph A. Austen, professor emeritus of history, known for his keen focus, depth of knowledge, and his far-reaching curiosity, passed away on Friday, August 23. He is remembered as a devoted member of the Committee on African Studies and his local South Side community.

Austen’s scholarly endeavors were driven by his focus on the dynamics of historical change in Africa, and how these impacted wider, global processes. He was generous with his time for others and pressed both students and colleagues to think comparatively, embark on original research, and to engage broadly with big questions. .

Austen’s colleague Jennifer Cole, professor in the Department of Comparative Human Development, described Austen as “very Chicago old-school.” She and others recall his regular and engaged attendance at UChicago workshops.

“Ralph was just an incredibly good colleague. He was tremendously erudite.”

“The University of Chicago has a reputation of being a very hard-nosed, tough experience, and it's a very rigorous place,” says former student Michael Gomez, now a professor of History and Middle Eastern & Islamic Studies at New York University. “I think that Ralph embodied that, if not epitomized that.”

Austen was born in Leipzig, Germany, and left when he was 2 years old. His father, Norbert Hans Oesterreicher, secured visas for the family to leave the country when he was arrested and detained by the Nazis — saying later that he was released because they thought he was too tall to be a Jew. The family lived for a year in Sweden before moving to New York in 1940, where they changed their last name to Austen. They moved from Flushing, Queens, to Great Neck, Long Island. As a young man, Austen wanted to travel, and he crossed the Atlantic again by working on a cargo ship alongside a crew of men from across the globe.

Austen earned his undergraduate degree from Harvard University, an M.A. from the University of California, Berkeley, and then returned to Harvard for his Ph.D. While working as an assistant professor of history at New York University in the 1960s, he met his future wife, Ernestine Stotter — also an educator — at a party.

Upon joining the University’s Department of History as an assistant professor in 1967, Austen became the first tenure-track historian of Africa to be hired by the school. It was a period of transformation on the continent, as colonial rule in many African countries ended in the 1960s and the world looked to better understand the effects of European colonization and the force of African social and political processes.

One of Austen’s most enduring legacies is his key role in establishing the African Studies Workshop at UChicago more than 40 years ago. This regular gathering was one of the first devoted to interdisciplinary graduate student training, and bringing together generations of students and faculty across the Social Sciences and Humanities disciplines to engage in scholarly debate and discussion. Austen actively participated in the workshop well into his retirement.

“The study of Africa at the University of Chicago, to the extent that it has been established and it has developed, that's due to Ralph,” says Gomez, also the founder of the Association for the Study of the Worldwide African Diaspora.

“It has grown, it has stabilized — and that was Ralph's work.” Emily Lynn Osborn, Associate Professor of History, who succeeded Austen in the department as a historian of Africa, agrees. “Austen launched the Africanist tradition at UChicago, and it is one that continues to thrive, in the department and beyond.” She points out that there are now three UChicago historians who specialize on this vast continent.

Ralph’s first book, Northwest Tanzania Under German and British Rule, was a colonial history of Tanzania, written in 1969. Over the next six decades he wrote, co-authored, or edited seven other books and published more than 100 scholarly articles and papers.

His writings included the early observation that Africa possessed a history “apart” from its colonization by European powers, with a rich history that is critical to how independent African nation-states emerged. In his first book, he described how the political project of independent Tanzania depended “not only upon the actions of Tanzanians in the present, but also on their understanding of the past.”

Credit: University of Chicago Photographic Archive, apf1 11857, Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

Austen’s studies pulled from the fields of economic, imperial, and cultural history, and included comparative analyses that brought Africa together with Europe and India. He explored many geographic regions, including Tanzania, Cameroon, the Mande world of West Africa, the Saharan desert, and the Atlantic world. For example, he studied the Duala coastal peoples in Cameroon and their role as brokers of politics and trade on the Atlantic coast over 300 years. He considered the trades in enslaved Africans across the Atlantic Ocean, as well as those of the Sahara and the Red Sea. Austen explored the continent-wide tensions of economic development and dependency, including how technology and disease facilitated and impeded European ambitions on the continent.

“There was a kind of restlessness to Ralph intellectually,” Gomez says. “It's not surprising that he kept finding new projects that were not necessarily related to former projects. And his research was never in terms of broad, theoretical inquiry — but far more granular.”

James M. Vaughn, a former student and now an assistant instructional professor in the Department of History, reflected on the time he spent with his teacher similarly, “I pursued a graduate field in the history of European overseas expansion and the making of global capitalism with Ralph,” he says.

“We spent countless hours discussing these subjects and he profoundly shaped my thinking about them. Ralph thoroughly read my dissertation and, after I received my doctorate, he read early drafts of my first book manuscript. He offered extremely insightful comments and criticisms on all my work. The most profound impact that Ralph had on my work was to make me think of any question of historical change in as global and as comparative a context as possible.”

Austen was also instrumental in the evolution of the Master of Arts Program in the Social Sciences (MAPSS), alongside his colleague, anthropologist John J. MacAloon. Austen considered it his greatest administrative contribution to the university, appreciating that MAPSS then functioned as a "teachers training program," largely for those going into secondary education — many in Chicago Public Schools — and providing a foundational understanding of the social sciences that would be taken out to the broader world.

His students and colleagues remember not just his active mind, but his active lifestyle: Austen traveled to the university by bicycle, even in the winters, and kept regular appointments with colleagues for a midday meal and chat — often toting the same, simple lunch.

“He had this incredibly rigorous, patterned life built around family and work in a way that I really admire,” Cole says.

One colleague, Paul Cheney, also in the Department of History recalls lunch gatherings with Austen and Osborn in one of their offices on the fifth floor of the Social Sciences building.

“He was almost compulsively sociable as an academic,” Cheney says. “He encouraged me to think comparatively. He was just curious about everything he did. And he had an amazing memory.”

Vaughn says Austen was always available for discussions outside of the classroom, and the direction of that conversion could shift to a variety of other topics, ideas, and concepts. Vaughn underscores that Austen set an example for himself and other students, encouraging them — by example — to develop a serious expertise as a scholar in their chosen field, while also being able to converse across the humanities and social sciences.

“Ralph was both a ‘scholar's scholar,’ in the sense that he had an incomparable expertise in his chosen field of study — African economic history — and a Renaissance intellectual, in the sense that he read widely, thought deeply, and participated in the life of the University across the social sciences and humanities,” Vaughn says.

Austen and his wife Ernestine lived in South Shore’s Jackson Park Highlands neighborhood for 50 years, where they raised their two sons, Jacob and Ben, and were active members of the community. Jacob and Ben attended public schools and graduated from Kenwood Academy. Austen joined the University of Chicago Hillel and later Hyde Park’s KAM Isaiah Israel. He taught English at the Hyde Park Refugee Project as well.

“He was an intellectual: deeply curious, very serious, very hardworking,” Cheney says. “But this is someone who knew how to put his work in its proper place. And he was a real family man and a community man.”

Austen is survived by his wife of 56 years, Ernestine; his sons, Jacob and Ben; his daughters-in-law, Jacqueline Stewart and Danielle Austen; his grandchildren Maiya, Lusia, Noble and Jonah; and his sister Judith.

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO