How redistricting has consequences for independent politics

A new U Chicago study finds city governments sometimes redraw ward maps to punish advocates of racial and economic equality.

By Sarah Steimer

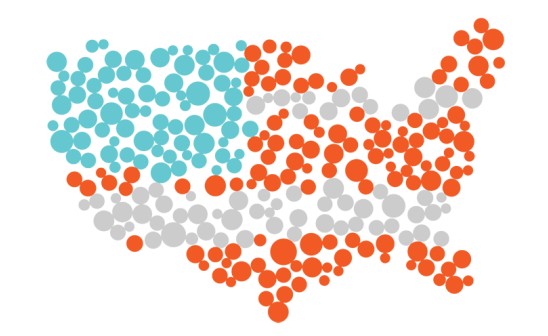

Gerrymandering and redistricting have been hot-button topics recently — especially as Democrats and Republicans vie for control of the House. Critics of the practice say it throws favor unfairly toward particular politicians or political parties in elections, helping to swing election outcomes. But a new study from U Chicago researchers shows the practice is also used by local governments to punish advocates for racial and economic equality.

The research team, led by Robert Vargas, an associate professor of Sociology, published their findings in Social Problems. The study, which has implications for independent or progressive political officials in particular, began with the simple question of what gerrymandering looked like from the 19th century to the present.

The study — focused on Chicago, Milwaukee, and St Louis — discovered four practices that local governments use to deal with politicians who push against the status quo. These tactics include suppressive redistricting, disciplinary redistricting, remunerative redistricting, and transactional redistricting.

“What really jumped out was that gerrymandering has not been along party lines in cities, it’s been along racial and economic ideological lines,” Vargas says. “Across all three cities, it was startling to us that redistricting has been used as a means of managing and socially controlling elected officials whose policy positions mostly aligned with racial and economic justice. Some of the most outspoken critics of local government, as it relates to issues of racial equity, equitable development, and the regulation of economic growth, these particular elected officials were targets of gerrymanders.”

Vargas uses St. Louis politician Sharon Tyus to illustrate the concept of disciplinary redistricting: Tyus served as alderman of the city’s 20th Ward from 1991 to 2003 but chose not to seek re-election to that seat because, in 2001, her fellow aldermen moved her ward from the city’s north to south side in a remapping. Vargas notes that Tyus, a black elected official, was a staunch critic of the mayor as it related to issues of racial equality in hiring of city jobs and for racial equity in economic development. Based on the study’s findings, it’s a prime example of redistricting used to discipline an elected official who pushes against the government.

The study used mixed methods to track and understand the movement of districts over time, then compared this data with archival research to determine what motivated these redrawings. According to Vargas, the research was broken into four steps.

First, research assistants obtained paper maps of the districts at libraries, which were then digitized using ArcGIS software for statistical analysis. Next, the team determined measured the distance that each district traveled after each redrawing. The third step involved data visualizations of each wards’ movements over time: How much did districts move, what were the minimum distances, and what were the maximum distances?

“Graphs showed the distribution of how far wards moved,” Vargas says. “What jumped out was that some hardly traveled at all for over a century and some, at certain moments of time, moved great distances — even from one end of the city to another.”

The final step was archival research, during which the team reviewed newspaper archives, policy documents, books, and city research undertaken at the time of redistricting in order to parse any related racial or economic turmoil.

“What stands out to me as the takeaway of our work is that the social conditions and outcomes of a community are not a mistake,” says co-author Christina Cano, AB '19 in Sociology and Creative Writing. “The ways maps are drawn are not a mistake — it’s no coincidence that Gold Coast, the wealthiest neighborhood in Chicago and one of the wealthiest urban neighborhoods in the country, has remained in the same ward for nearly a century. Maps have historically been used as a method to allocate and withhold power, and redistricting is just one of the processes through which certain racial and economic hierarchies are maintained.”

According to Vargas, the study could act as a warning signal to elected officials, particularly those who are outspoken on matters of race or economic equality. Should these politicians fail to form coalitions or other alliances that could help them maintain their ward’s boundaries, they risk being gerrymandered out of a job and the power to enact change.

“Gerrymandering is often perceived as a partisan political issue, but at the city level — where one party tends to dominate — redistricting is used as a potentially devastating tool against movements for change within the party.”

Another implication of the study, he says, is providing fuel to the argument for tasking independent groups with redrawing districts — versus elected officials. It’s a shift that would bring more fairness and impartiality to the practice, reducing the likelihood of redistricting being used to punish advocates for social change.

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO