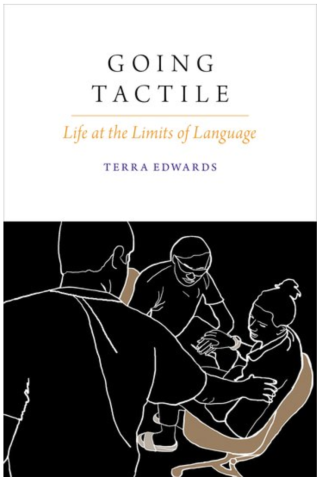

A new book on the DeafBlind community considers communication the limits of language

Going Tactile is the product of almost 20 years of Terra Edwards’s anthropological research and engagement with the community.

By Sarah Steimer

As deaf individuals lost their sight in the particular DeafBlind community Terra Edwards was studying, she discovered that an entirely new language emerged — one that doesn’t try to negotiate with a seeing world, but is rooted in a tactile world. In her new book, Going Tactile: Life at the Limits of Language, Edwards, a linguistic anthropologist in the Department of Comparative Human Development, explores the existential and environmental factors that impact language for DeafBlind communities.

The book is the culmination of almost 20 years of anthropological engagement with DeafBlind communities, mostly in Seattle as well as in Washington, D.C. Prior to graduate school, Edwards was trained as a professional interpreter for the DeafBlind community.

Within this particular DeafBlind community, Edwards explains, individuals are born deaf and have a genetic condition that leads to a slow progression into blindness. This means they acquired American Sign Language as deaf children, but as they become blind, this visual language is increasingly difficult to use. As this happened, certain problems would arise. For example, a group conversation would require cueing to know who’s talking next, and interpreters such as Edwards would step in and prompt or offer additional information to make the interaction or experience work out. As people become blind, more and more descriptions of the environment are added, which are meant to stand in for the environment itself — but a person can't actually live in a description, Edwards explains.

“You can get lost in a book, she says. But “what we discover from my research is that there's a limit to that. It turns out that it's an empirical fact.”

She gives the example of the COVID pandemic: Connecting with people via phone or video calls or otherwise couldn't stand in for a true social life. There’s a limit to what representations of the world can do, versus actually living in the world. As a deaf person began to go blind, the solution was to rely more and more on sighted people to translate and relay information. “And what I argue in the book is that that led to existential collapse,” she says. “It led to the impossibility of existence.”

As she dove into the changes in language at this stage, she initially thought she would be studying the strategies that individuals used to make American Sign Language work. “On some level, language is an abstract cognitive system, and it shouldn't matter what modality it is expressed or received through,” Edwards says. “But it's also kind of an open question about which level of abstraction we should study that system at, and at a certain level, it does become important what modality it’s being transmitted in.

“So I was interested in where the problem of modality entered for people, in a practical sense. To what extent was their language still viable, even if the sensory modalities that related it to the actual context of its use were reduced or gone.”

In her first summer returning to the DeafBlind community in Seattle as a researcher, Edwards started to witness a change in interactions she hadn’t previously noticed: She watched an interpreter talking to a DeafBlind person, who in turn was correcting the interpreter and saying, “You're saying that wrong.” At the time, it seemed unusual, she says. Sighted people were the ones who were the “experts” on communication because they were able to use a visual language, and DeafBlind people were constantly in the position of receiving knowledge about the world. In this moment, however, the DeafBlind person was taking a stand and saying, “No, you're getting something wrong.”

In that moment, she also noticed that what the DeafBlind individual was doing was radically different, language-wise; it was a form of pointing, but on the other person's body, which was also a difference in orienting to the environment that was being pointed at.

“I thought I was going to study how they were changing American Sign Language, but I ended up studying how a new language emerges,” Edwards says. “That is really the basis of all of my research since then. It's about language emergence and the existential and environmental foundations of language emergence: how we exist in the world, and how our modes of existence actually give rise to particular ways of representing the world.”

This whole process started with two DeafBlind women, who were in positions of authority within this community, who asked the question of: Why are we depending so much on sighted people? Why don't we just communicate with each other? In response, they organized events where they didn't provide interpreters. Slowly, DeafBlind individuals let go of ideas about what they're missing out on, and they focused on what was already there. The premise — which was also philosophical in nature — was that everything in the world is also tactile, and so there's no reason why someone really needs vision or hearing to live.

The resulting language was a process of uncovering obstacles and relaxing sighted social constraints on touch. A sighted person can distinguish between words in American Sign Language based on the backdrop of the signer’s body, but that context isn’t there for a DeafBlind individual. The first step in the process became about feedback: If a person couldn’t show they understood by nodding, they would tap on the other person’s body to convey they were following along. Providing feedback allowed them to understand when understanding was not taking place. And out of that process, one of the systematic changes was that instead of one’s own face and body as the backdrop, people would use the other person’s body as the backdrop for distinctions.

“That may seem like a small thing, like, ‘Oh, you just take the language off of here and put it on there,’” Edwards says. “But one thing leads to another, and pretty soon you've got a completely different system. That was the beginning of this radical grammatical divergence between the two languages.”

She describes the process as “almost magical”: Much of the information we receive from the world is already tactile, we just stop perceiving information in that way. But that has to do with social and historical phenomena, it isn’t a physiological problem. Once those social and physical barriers are removed, the language uncovers itself.

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO